While not of the caliber of Chandler or Hammett, Keene’s working-class novels show his talent for telling intriguing mysteries at a breakneck pace.

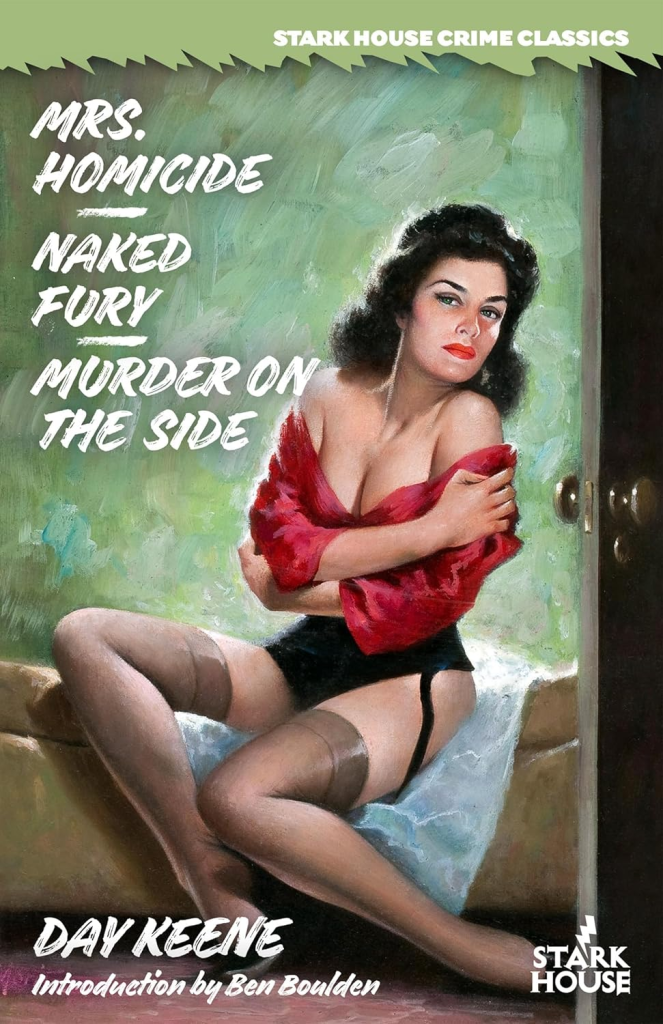

As soon as I read, “Dead men are my business,” on the first page of Day Keene’s 1953 novel, Mrs. Homicide, I knew it was going to be a good ride. The line erupted from the book and into that great stratosphere running on pulp fumes that propel this narrative. Keene fills his novel with all the escapist trappings of pulp fiction. However, his work, like many other writers of the time, runs deeper than mild pulp exploitation. Keene was a hardworking author for the pulps and good at his job. Yet, there is an aesthetic in all three of the novels in the new omnibus by Day Keene published by Stark House Press that is not present in many other forgettable contemporaries. Ed Gorman said Keene was in touch with his “inner loser,” as Ben Boulden quotes in his introduction. This is evident as Keene writes about lost and unstable men, and equally dysfunctional women with authenticity, empathy, and raw insight. The omnibus includes Mrs. Homicide (1953), Naked Fury (1959), and Murder on the Side (1962).

The term “dead men are my business” is applicable to the Mrs. Homicide as Detective Herman Stone is hired to solve murders of dead men, but in a sense this phrase is metaphorically applicable to my own work as a critic as well as other critics in the field. I am writing about lost and forgotten, long deceased talented men that are only now getting attention with a surge of reprints. Dead men are my business as well. Many long dead writers of pulp have undergone a reevaluation in recent years. Additionally, pulp has been analyzed from different lenses since its origins. The way sexual politics, gender roles, and ethnic identities are dealt with in literature has obviously undergone tumultuous changes since the hey-day of pulp. It is interesting to look back and to see the robust change of relevancy and irrelevancy in the works of pulp authors like Keene.

Ben Boulden’s introduction to the Stark House Press edition discusses Keene’s career and places it in the context of the pulp fiction golden years. Wildly politically incorrect and outrageously misogynistic at many points, these novels by Keene were entertainment of the proletariat of the 1950s and early 1960s, as historically pulp fiction has been. Now in retrospect, critics look to see what can be gleaned from the gilded pages of rapid-fire, staccato dialogue that populates so many of the books by Keene and others of the time.

Boulden explains that Keene: “tended to chronicle male insecurities and dissatisfaction: cheating wives, mid-life crises, and the betrayal of friendship.” Mrs. Homicide has to do with a murdered man, and a cheating wife. The cheating wife happens to be Detective Stone’s and she is being framed for the murdered man . Stone is determined to prove his spouse’s innocence even if he has to challenge the entire police force to do it.

The set-up is there. There is little exposition as is typical of these types of novels. Yet, Keene writes urgently, almost frantically. Most pulps of the era had to move fast to keep the attention of the working masses. Yet, Keene’s prose is meaner than others I have encountered, including the infamous Mickey Spillane. It appears that many forgettable pulp authors all blend together, but occasionally there are a few that make it from trash heap. Chandler, Hammett, Thompson, and later, Goodis, rose to recognition, while writers like Keene faded away. It then becomes necessary to reevaluate writers like Keene, who were the “real deal” in terms of hardcore pulp. Keene had bylines in all of the popular magazines of the time. He also has many novels to his credit.

Naked Fury is a wild romp. It is unintentionally, hysterically irreverent as are all three novels in retrospect. Yet, Keene is deadly serious. The story also features a politician as the strong male protagonist. The plot follows a man who witnesses a hit-and-run accident and then is murdered by some thugs who tried make him change the color and make of the car in his story for reasons that will unfold throughout the story. We are then introduced to yet another pulp tough guy, Big Dan Molloy. I was thinking that Sterling Hayden could have played him back in the day. It has Molloy trying to nab a hit-and-run driver whose crime is pinned on the owner of the supposed car, Molloy’s gal. Dan is a politician whose political influence connects him to many powerful and dangerous friends. He also is well liked by immigrants in the city at that time and anyone who is of the lower class. Keene does not use culturally sensitive language talking about ethnicity, which, again, was typical of pulp fiction of the era. Dan Molloy is more enigmatic than you might find in Mike Hammer stories.

Keene writes about lost and unstable men, and equally dysfunctional women with authenticity, empathy, and raw insight.

Murder on the Side is probably the most literary of three novels. Larry Hanson is the protagonist in this one and the plot is more interesting than the other two novels, and Keene tones down the beginning of the novel with Hanson reflecting on his life of regrets. In this novel, Hansen is a bored, middle-aged engineer who gets involved in a murder rap which includes his beautiful secretary and her recently released, ex-con boyfriend. Hanson is more nuanced and more reflective of an anti-hero. While he is the stand-in for the obligatory male pulp protagonist, he also seems to have more intellectual prowess and sensitivity than the previous protagonists. The first two novels assault the senses from get-go while Murder on the Side rises to a crescendo. All the novels display a mastery of hardboiled language and pacing that is hard to resist digging into.

While not of the caliber of Chandler or Hammett, Keene’s working-class novels show his talent for telling intriguing mysteries at a breakneck pace. This is what the pulps of the time period were all about, and Keene does a fine service to pulp fiction. He transcends with interesting language and phrasing, enigmatic and unlikely heroes, unique storytelling arcs, and with his unabashed mission to tell a forceful narrative with rigorous language and strong dialogue. It is for these reasons Day Keene’s work makes him a pulp non-canonical gem to be continued to be studied and read by critics and readers alike.

William Blick is an Assistant Professor/Librarian at Queensborough Community College. He has published articles on film studies in Film International, Senses of Cinema, Cineaction, and Cinemaretro and on crime fiction at Retreats from Oblivion: The Journal of NoirCon. His fiction has appeared in Out of the Gutter, Pulp Metal Magazine, and Pulp Modern Flash.