He’s so concerned for the way he thinks things should be, he forgets a man can’t move something as big as the Moon….

I am standing at the foot of Galata Tower very near the place where, a few years ago, on a November night that was exceptionally cold, a body lay on the paving stones. I happened to be passing as a policeman was pulling a sheet of plastic over the remains with hardly more care than you would take to spread a cloth over a table. I overheard someone say that the dead man had jumped from the balcony near the top of the tower. Someone else, bearded and fingering prayer beads, muttered that only Allah has the right to take life as it is only Allah who bestows life. I was glad for the winter weather; anyone’s eyes could become watery on a night with such a bitter wind whipping through it.

Made of rough stone, Galata Tower dates from the early centuries of Byzantine rule. It is tall enough, even in an Istanbul that has been revised countless times by architects, to be a landmark to ships passing through the Golden Horn. The top comes to a point like a minaret, but, as it is stoutly built, it has none of the minaret’s slender grace. This much you could find out for yourself from a postcard or a photograph. What a photograph can’t tell you is why a young man jumped from the tower on that November night. Although I’m not as comfortable with words as I am with numbers, I’m going to try.

Erjan and I had been friends since high school. Even then he had his eyes on the best-looking girls in our class. He himself was no beauty. By the time he was 26, he’d already lost a lot of hair and had permanent swellings under his eyes so that they seemed to be smiling even when he was unhappy. This was often the case since he didn’t like working in his father’s bakery. While he wasn’t pleased that he was balding, he was more likely to complain that his nose was too big and had too much curve to it, as if for no other reason than to defy a good sense of proportion.

“It’s fine,” I always told him although if he’d been chipped from marble, I’m sure his nose would have been chiseled down a bit and straightened a little. He wasn’t remarkable in any way—except to me.

I don’t make friends easily. It takes persistence. There may be weeks of Hello, good to see you before I don’t feel the need to hide behind a tense smile. I may hear I like the dress you’re wearing or Don’t you look nice today? a dozen times before I begin to believe it.

I don’t know why Erjan took an interest in me, but I sometimes saw him smiling at me in math class, his smile accentuated in a peculiar way by those swellings that, back then, were just creases underlining his eyes.

I was a quiet girl who didn’t attract attention. My black hair falls to my shoulders without a curl or a wave. I’m not very tall, and because I’ve never had much of an appetite, I’ve stayed thin. I looked nothing like those girls who lightened their hair to be more Western, or for the striking contrast with their dark skin. These were the girls who went to the bathroom and secretly put on eyeliner and mascara; make-up, dangling earrings, and long hair that wasn’t properly tied were all forbidden in high school.

I knew Erjan didn’t want me as a girlfriend, but he kept smiling and getting me to help him with his homework and whispering jokes in class that I couldn’t help laughing at. Every now and then we would sit down together in the school cafeteria for lunch. For reasons that weren’t clear to me at the time, he decided that my 18th birthday should be one I would never forget.

When I looked at him, he made a face that insisted on silence.

On a breezy evening in August, a boat took us along the shores of Istanbul. By the time night had settled in, the city glittered as much as the sky over the Bosporus. Music and laughter floated out to us from the bars and night clubs along the water’s edge. We enjoyed being close enough to hear them but distant enough to feel that we were on our own drifting island.

Later, I drank wine for the first time in my life—that’s probably why I danced in the open air with couples I didn’t know and even sang a little with the violin player who had a shirt pocket bulging with tips. As the boat came to the Bosporus Bridge, I told Erjan he should have taken his girlfriend out for a night like this.

“Oh I will. But I’ve known you longer.”

The bridge blocked our view of the stars as we went under it.

“Besides you don’t have a boyfriend, and you only turn 18 once.”

All these years later, I’m still surprised.

After high school, Erjan and I saw each other much less, but at least once a month I would look over the accounting entries for the bakery. Neither he nor his father was very good at balancing debits and credits so, after his father’s bookkeeper retired, I took over the task. It became habit, once I had balanced the ledger, for Erjan to take me out to dinner. We often met at a restaurant near Galata Tower because it wasn’t far from the dingy office where I worked.

“I smell like a loaf of bread today, don’t I?” he would say.

Other times, I noticed, his scent was more like sugar that has to be scraped from the bottom of a pan.

He would throw his hands up in frustration. “It’s bad enough I work in a bakery, but do I have to bring it with me wherever I go, too?”

I could never tell Erjan, but I thought these smells suited him.

One evening in June, when Erjan’s hands were spiced with cinnamon, he brought me a complaint that wasn’t his usual grumbling. We were sitting in the restaurant where we usually went for our dinners. The walls, of brick and stone, were almost as old, I’m sure, as Galata Tower. We were down to our coffee by this time and, an elbow on the table, he rested his cheek on a fist. “Has anyone ever fallen in love with you?”

“There was Alp when I was 10 years old. Does that count?”

“What about Yujel?”

I sighed. “Yujel thought he was.”

“There, you see?” His head came off his fist. “You exist. I don’t.”

“Why do you say that?”

“If no one has fallen in love with you, how can you exist?”

“Well, maybe Yujel fell in love with me, but you know very well I wasn’t in love with him in the least. If he hadn’t asked me out so often, we wouldn’t have been together in the first place.” I looked down at the white tablecloth. “Not much of a loss for either of us.”

“But at least you had someone who thought you were worth marrying. That’s never happened to me.” He sipped Turkish coffee from a tiny cup. “There was a poet we had to read in high school—I don’t remember his name—he wrote something about a moon with no sun to make it visible at night … with no earth anchor it. Does a moon like that really exist?”

Mentioning the Moon reminded me of something that I thought would take his mind off the subject. “Do you remember that story about Nasrettin Hoja, about seeing the Moon in a well?”

Erjan rolled his eyes. “Not the Hoja. Haven’t you had enough of those stories?”

“We all have, I suppose, but I like this one … he sees the Moon reflected in the water at the bottom of a well, and he becomes frantic wondering how he’s going to get it out.”

“No, I don’t think I remember this one …”

“Well, I don’t remember it so well either. I only remember that the Hoja gets a chain with a hook on the end of it and drops it into the well. It gets caught on something at the bottom so he jumps up on the well, spreads his legs over the mouth, and pulls as hard as he can. The hook suddenly comes free, the chain flies up, and he falls over and lands on his back. Now that he’s looking up, he can see he’s done it, the Moon is in the sky again.”

“Where it was the whole time.” Erjan nodded and turned his coffee cup upside down in the saucer as if someone were going to lift it and read his fortune in the muddy grounds. “So what’s the point of this story?”

“I don’t know.”

Erjan let a puff of cigarette smoke go up toward the ceiling. “Why do you like it so much?”

I shrugged. “I guess the idea that he … he’s so concerned for the way he thinks things should be, he forgets a man can’t move something as big as the Moon.”

“I think you’re confusing him with Archimedes.”

I thought I’d succeeded in distracting Erjan, but from the way he smoked his cigarette, I knew he was still thinking of himself as unlit by any sun, with no sky in which to appear.

That evening, after he’d paid for dinner, we stopped in a music shop on Istiklal Avenue and Erjan did something very strange: he slipped a cassette into his pocket. When I looked at him, he made a face that insisted on silence. When we were back on the cobblestones of the avenue, I asked him what he thought he was doing.

He pulled the cassette out of his pocket. “You can’t arrest someone who doesn’t exist.”

“Well that’s a good idea then. Maybe when you’re sitting in a police station you’ll realize how wrong you are”….

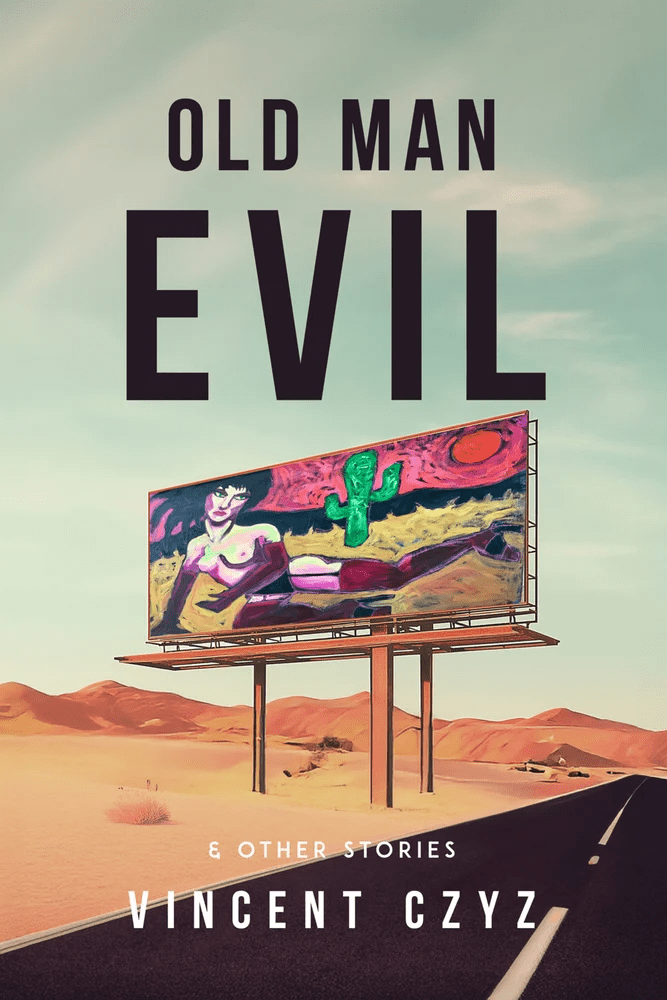

The above was excerpted from Old Man Evil & Other Stories by Vincent Czyz (Running Wild Press, 2025). All rights reserved.

Vincent Czyz is the author of two short story collections, one of which won the 2016 Eric Hoffer Award for Best in Small Press, two novels, a novella, and an essay collection. He is the recipient of two fiction fellowships from the NJ Council on the Arts, the W. Faulkner-W. Wisdom Prize for Short Fiction, and the 2011 Capote Fellowship at Rutgers University. His stories have appeared in Shenandoah, AGNI, The Massachusetts Review, Tin House, Copper Nickel, and Southern Indiana Review, among other publications.