Samuel drives his Taurus through northwest Magnolia Beach. On Saturdays, he plays the car radio. Wednesdays, he likes the silence….

Wednesdays and Saturdays, Samuel Fulton runs the Presidents.

It started as a simple routine but is now edging its way into ritual, gaining emotional and psychological weight with each run, Samuel leaving his townhouse at Bayview Manor late in the afternoon and taking Hanover Avenue until it intersects with Fremont Street in northwest Magnolia Beach, Samuel then driving three blocks and pulling into the lot of the Parnassus Diner where he eventually takes a window seat and orders black coffee as a preamble to the unvarying order of a cheeseburger platter, Samuel, in the interim, paging through The Magnolia Beach Monitor and trying to acclimate himself to what he has yet to see as or call home since his wife Glenda and he moved there fourteen months ago.

It’s a Wednesday, so his waitress is Shirley. Saturdays, it’s Jena.

Shirley’s in her early forties, at least thirty years his junior, with two ex-husbands in the wind and three grown children, only one of whom stays in touch beyond birthdays and holidays. She has a kindly smile, a smoker’s cough, sun-cured South Carolina skin, and pale blue eyes fanning into laugh lines. She’s dating the owner of Tommy’s Towing Service but claims it’s not serious.

Shirley pours his coffee. “Any change?” she asks. That, too, has become part of the ritual. It’s followed by Samuel shaking his head no and then thanking her for asking.

Fifteen minutes later, Shirley brings his cheeseburger platter. Samuel sets aside his newspaper. He spreads a napkin across his lap and turns down a refill on the coffee. He eats slowly, with measured bites, and when he’s done, he slips the tip beneath his plate, takes his bill to the front register, and pays up. Before leaving, he turns the knob on a squat metal canister, and a wooden toothpick drops into a curved slot. Samuel tucks the toothpick in the corner of his mouth and leaves.

Outside, February still can’t make up its mind if it’s late winter or early spring, the days continually seesawing between freeze and bud, and Samuel Fulton stands for a moment in the parking lot and looks at an uneasy skyline full of mismatched light and mottled gray cloudbanks. Right then, he misses the Midwest and the clear demarcation of seasons, days that squarely fit the calendar.

For the next twenty minutes, Samuel drives his Taurus through northwest Magnolia Beach. On Saturdays, he plays the car radio. Wednesdays, he likes the silence. This quadrant of the city is blue-collar and old-school middle class, its neighborhoods as high as upward mobility can or will ever take its inhabitants.

Near Delray’s Small Engine Repair, a middle-aged couple is walking a brown and white dog. They wave as Samuel passes, and he lifts his hand a little late in a delayed reaction. He has not gotten used to the South’s habit of waving at strangers. He can understand and appreciate the sentiment behind the gesture, but as a Midwesterner who’d used his waves for people he knew, the whole thing still feels a little too indiscriminate.

Samuel slows as he drives past St. Matthew’s Lutheran Church. He looks at the large red doors fronting the church. He knows what will happen when those red doors open on this particular Ash Wednesday evening. He can already feel the rector’s fingers on his forehead and then hear the words that accompany the sign of the cross: Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return.

Samuel, however, doesn’t wait for those doors to open. At seventy-one, he knows all too well that dust is a truth that he and most of the residents at the Bayview Manor complex wake up to and put to bed each day.

As Samuel gets back on Fremont, the sky suddenly collapses under the weight of the clouds, and he hits the lights and wipers on the Taurus. The rain arrives at a sharp slant, growing hard and insistent. Within two blocks, he has the defroster on high. The wipers move like a set of arms thrown up over and over in surprise or surrender.

He thinks about turning around and heading back to the Bayview complex, but Madison’s coming up on his left, and Samuel taps the blinker and begins to run the Presidents, following Madison to Roosevelt and Roosevelt to Jackson and Jackson to Washington and Washington to Harrison and Harrison to Taylor and Taylor to Jefferson. The neighborhood is World War II vintage, a mix of one- and two-story homes, most wood or asbestos-sided and bounded by tree-lined sidewalks fronting the network of streets running in strict right-angled grids.

There’s a run of thunder off to the west, and by the time Samuel makes Jefferson, it feels as if he’s driven into an eight-hundred-and-twenty-seven-mile-long memory, one that’s been in place for close to fifty years.

Right now, for all intents and purposes, he could have been back in Ryland, Ohio, newly married, flush with plans and promises, and about to turn onto Alexander Street and into the driveway of the first home his wife Glenda and he had owned.

519 Alexander or 805 Jefferson. A white wood house that fit either address.

Samuel glances down at the dash. The Service Engine Soon light surfaces and flickers and then holds. He slows, then pulls in next to the curb.

The Taurus’s engine shudders and cuts off.

Samuel continues to scramble for the phone…. When he looks up, the man and the young woman are standing just outside the passenger door….

The front door of the white house bursts open. A young woman in a black bra and red panties starts running at a diagonal across the front lawn. She’s carrying a pair of high-heeled shoes in her left hand.

A tall man wearing khakis and a pale blue shirt chases after her.

The woman looks back over her shoulder. She slips and falls and gets up again. She’s lost one of the shoes she’d been carrying.

The rain begins to pick up again, thin silvery sheets that the wind turns inside out.

The woman is running toward Samuel and the Taurus. She’s yelling something, but Samuel can’t make out the words.

The man closes in, catching up and grabbing a fistful of hair. The woman tries to break free, but finally can’t. The man starts dragging her back toward the house.

Samuel hits the horn on the Taurus once, then twice more. The man pauses, surprised.

Samuel scrambles for his Tracfone, but in his haste, drops it. He’s not sure if it’s on the floor or between the console separating the driver and passenger seats.

The man has reversed course. He’s now dragging the young woman toward the Taurus.

Behind him, the front door of the house opens again. Two more women come running out.

The man looks over his shoulder. Samuel keeps searching for the Tracfone, but his fingers feel like they belong to someone else.

The two women are fast. They make the sidewalk, then street, and disappear behind a rippling curtain of rain.

Early evening breaks under the weight of the weather. Samuel continues to scramble for the phone.

When he looks up, the man and the young woman are standing just outside the passenger door.

The man’s hand is still wrapped in the woman’s hair. He tenses and keeps his arm rigid, pushing her face against the passenger window. The woman’s features are flattened and mashed on the glass and at the same time are obscenely animated by the rain running around them.

Samuel’s hand bumps into the phone. He grabs and lifts it and punches in 9-1-1.

The man, younger than Samuel originally thought, begins tapping on the passenger window. He then lifts his index finger, moving it left to right and right to left, metronome style, signaling Samuel to put down the phone.

The operator comes on, apologizing for the delay because of the volume of weather-related calls, and asks Samuel the nature of his emergency.

Before Samuel can reply, the young man places a hand on either side of the young woman’s head, and then with an abrupt twist, like someone trying to break a stubborn seal on a jar, he snaps her neck.

The young man lifts his hands, and the woman disappears.

Samuel can’t believe what he’s just witnessed. The taking of a life should have been more concrete and horrific. Instead, it feels dream-like, soft at the edges, like something the rain delivered.

The Tracfone drops Samuel’s call to 9-1-1.

The young man tries the front and rear doors, and when he finds them locked, he begins tapping on the passenger window.

Samuel keys the ignition. It clicks and grinds. The Service Engine Soon light comes back on.

The tapping stops.

Samuel looks over. There’s a pair of hands, palms open, wiping at the glass, clearing rain, and then a face appears.

The ignition catches. Samuel drops the Taurus into Drive and hits the gas.

It’s not until he’s made the corner of Jefferson and Taylor and taken a hard left that Samuel, corralling his panic and confusion, suddenly realizes the man got a better look at Samuel than Samuel did at him.

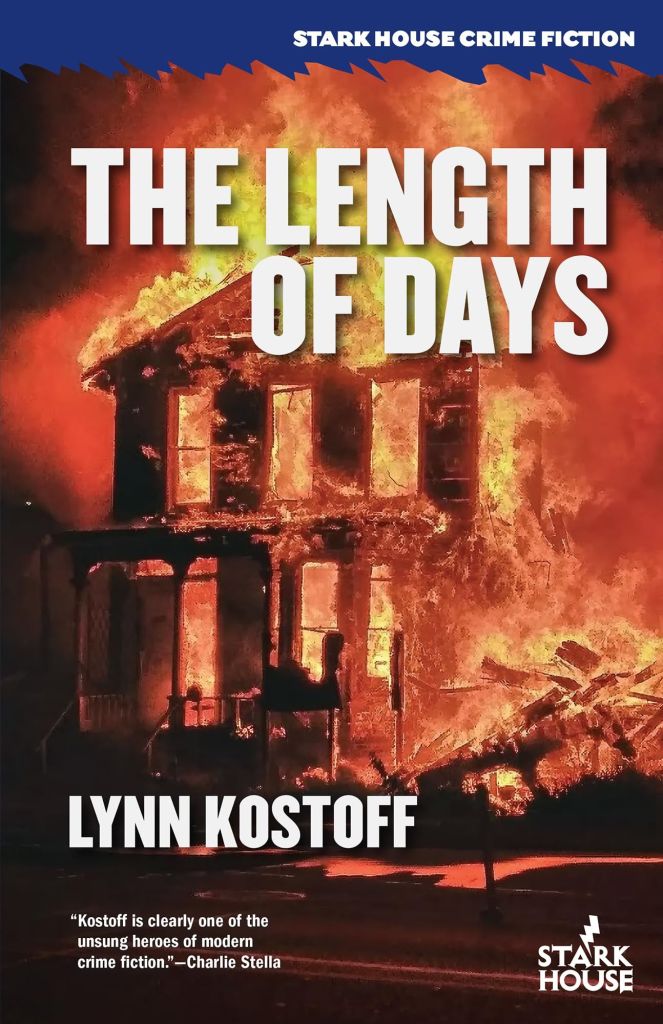

The above was excerpted from The Length of Days by Lynn Kostoff (Stark House Press, 2025). All rights reserved.

Lynn Kostoff was born in Moultrie, Georgia and raised in Northeastern Ohio. He attended Bowling Green State University for both his undergraduate and graduate degrees. Along the way to becoming a crime writer and English professor, he worked as a truck farmer, gardener, janitor, hospital orderly, and steel mill laborer. He has taught at Indiana State University and the University of Alabama and is retired from Francis Marion University in Florence, South Carolina where he was the Writer‐in‐Residence.