David and his collaborators on this graphic novel deserve credit for taking some detours and tangents that make their book distinctive…. But those pieces aren’t enough to overcome some fatal flaws….

In his introduction to this new graphic novel adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s novella Trouble is My Business, versatile author Ben H. Winters makes a case for the worthiness of creative works that are updated versions of past classics, done via an alternate media. He acknowledges common criticisms of such efforts, like “what do they add to the original?” and “what if they tarnish the source material in some way?” But he brushes those qualms off, averring that there’s always some value in an artistic re-imagining of someone else’s creative work from an earlier era. His argument is convincing, in and of itself. But the above-mentioned issues some take with such adaptations are valid, particularly the “what does it add?” question.

Trouble is My Business, the original work, is a long story featuring Chandler’s signature private detective Philip Marlowe. It’s the title story in a collection of a handful of Chandler novellas compiled in 1950. In the tale, the jaded, wisecracking, emotionally detached yet ultimately conscientious SoCal-based gumshoe takes on a case farmed out to him by another operative. There’s an alluring redhead who employs her feminine wiles in enticing amorous suckers into running up large debts to her boss, the kingpin of a gambling racket. The wealthy adoptive stepfather of one such sucker caught in the shill’s trap wants her stopped. It’s up to Marlowe to see if he can free the aged tycoon’s stepson from the femme fatale’s seductive yet perilous web. Of course, as the detective at work is Philip Marlowe, he doesn’t take the background info on the case at face value and will see for himself what’s what here, no matter who that bothers or endangers, including himself.

Chandler’s novella is one of several such works he produced over his relatively brief but ridiculously fruitful literary career. The story has all the usual elements that make Philip Marlowe tales work so well. It’s one that can please a Chandler fan to an extent, even if it lacks the depths of full-length Marlowe novels like Farewell, My Lovely (1940) and The Long Goodbye (’53).

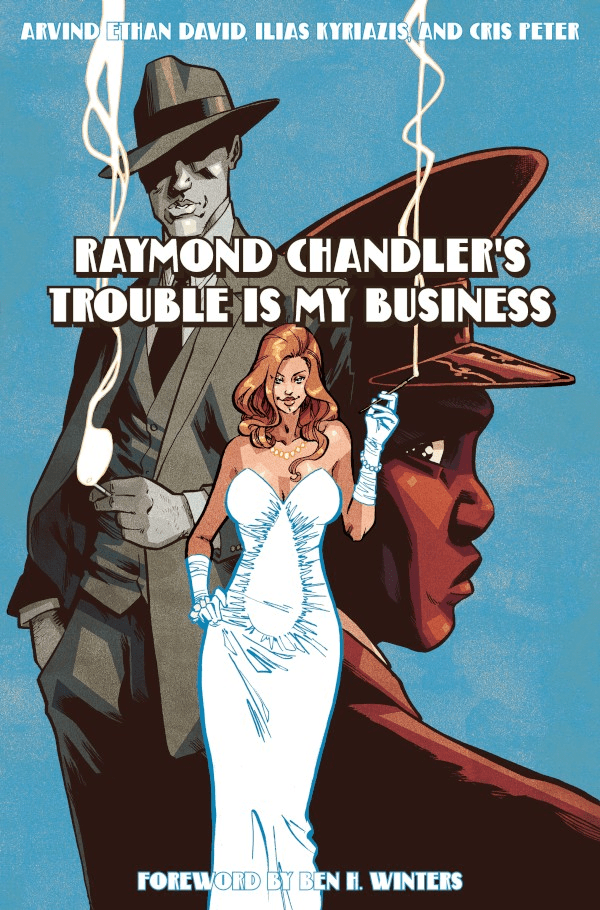

It’s a sizable work, one that needs careful handling. The biggest problem with the new graphic novel Raymond Chandler’s Trouble Is My Business (by Arvind Ethan David, Illias Kyriazis, and Cris Peter, from Pantheon Graphic Library) is the image of Marlowe. Anyone who admires Chandler’s writing knows that it’s the character of his serial P.I. that drives the books. Yes, the crime plots are intriguing and suspenseful; yes, the other characters are colorful and memorable; yes, the physical and emotional atmospheres the poetically minded scribe created have much to do with the overall pleasing reading experience. But it’s the richly evocative personality of the complicated man that is Philip Marlowe that’s the most central aspect of those stories. And the Marlowe that appears on these pages just doesn’t convey such character. He’s drab and indistinct. He didn’t need to look and act like the classic cinematic portrayals of the detective by the likes of Humphrey Bogart, Dick Powell, or Robert Mitchum. It would’ve been fine if his appearance and behavior were a liberty-taking leap like Robert Altman’s slovenly, mumbling vision of Marlowe as played by Elliott Gould, in Altman’s film adaptation of The Long Goodbye (1973). But the Marlowe in this graphic novel doesn’t come off as much of anything at all. His look is generic, and his words and actions lack depth. He’s more like a nondescript square-jawed detective you’d find in a throwaway old crime comic book tale than the always interesting character in Chandler’s writing.

Often feels hectic, unnecessarily hurried. What was the rush?

Another issue to be taken with the adaptation is how the story’s told. It often feels hectic, unnecessarily hurried. What was the rush? One shouldn’t approach a graphic novel hoping or expecting it to read like straight text in a traditional literary work. It’s a different medium, with its own separate possibilities and limitations. But a book such as this still needs things like pacing and building of momentum. And this one too often comes across as scrambled. Will someone who’s never read the Chandler novella experience it that way? I can’t say. But, while not every panel or page seemed chaotic to me, I too often felt like it was more a mad rush to get all the necessary words across the pages than a measured effort to tell a good yarn in a compelling manner.

David and his collaborators do deserve credit for taking some detours and tangents that make their book distinctive, like including sidebars that tell brief life stories of side characters and allowing the femme fatale to narrate in places, so it’s not all just Marlowe’s POV. Those touches are smart and innovative, and yes, because of those aspects, it can be said that the graphic novel does add something to Chandler’s story. But those pieces aren’t enough to overcome the above-mentioned fatal flaws that make this an unsatisfying read in the end.

Brian Greene writes short stories, personal essays and critical pieces on books, music, film and visual art. His features on noir fiction and films have been published online by Criminal Element, Crime Reads, Literary Hub, The Strand, Crime Time, Crimeculture, Mulholland Books, and others, and in print by Stark House Press, PM Press and Paperback Parade. He lives in Durham, North Carolina. briangreenewriter.blogspot.com/Twitter: greenes_circles