“It’s hard to discern where Woolrich left off and Block took over. Credit Block for his ability to seamlessly provide that continuity in the text….”

Cornell Woolrich (1903-68) liked to write about the repercussions that can result from the effects of accidental deaths by gunfire. That kind of construct is involved in his acclaimed jazz age 1940 novel The Bride Wore Black (which was made into the excellent 1968 film noir of the same title, directed by Francois Truffaut and starring Jeanne Moreau). In that story, a woman – whose new groom was inadvertently shot to death just after their wedding ceremony – becomes obsessed with tracking down and seeking revenge on those she believes are responsible for her beloved’s untimely demise.

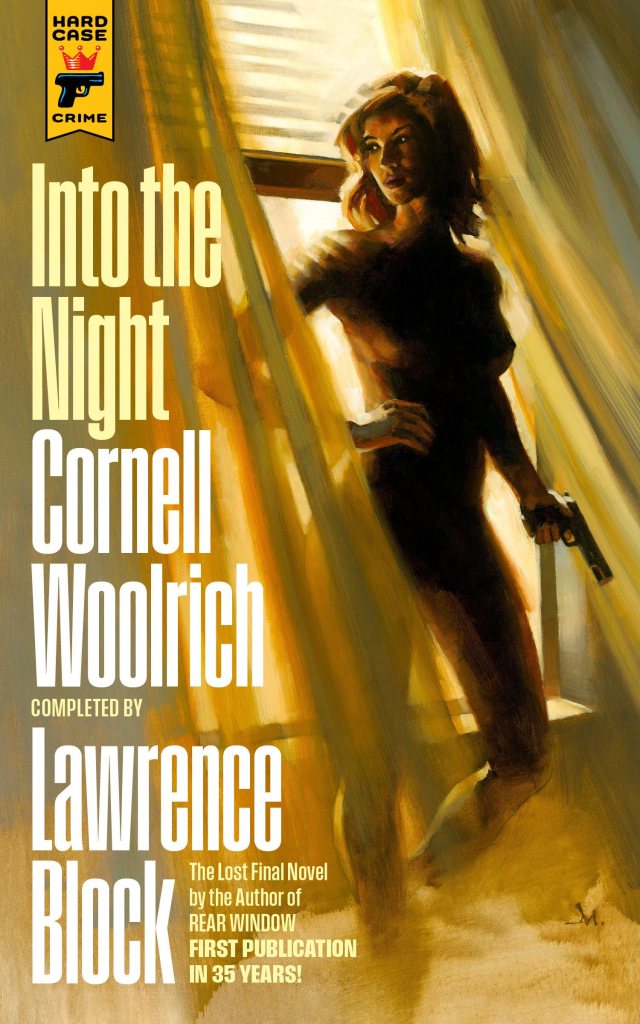

Similarly, Woolrich’s noir novel Into the Night, which was left unfinished when the brilliant yet personally troubled author passed away, concerns a chance fatality induced by a bullet. The story, which is set in 1961, opens with a depressed young woman named Madeline Chalmers, who happens to own a handgun, contemplating suicide while in her home alone. She doesn’t pull off the deed, yet she accidentally fires the weapon, sending a shot out into the street and killing an innocent passerby. No witnesses were on hand to see from where the gunshot originated, and the police ultimately assume the killing to have been the result of a something like a random drive-by shooting. So, Madeline is seemingly in the clear as far as criminal prosecution goes. But the guilt she suffers over ending the other person’s (also a young woman) life is its own kind of punishment; and it drives her to extreme actions, such as painstakingly learning about the deceased’s life story and taking huge personal risks while seeking to settle scores on the late woman’s behalf with those who were nemeses in her personal affairs.

In 1987, nearly two decades after Woolrich’s death, Into the Night was finally published. But how, you ask? With the able help of Lawrence Block (b. 1938), another accomplished crime fiction master, who was brought in to complete the manuscript.

“Otto Penzler chose me for the job,” Block told me over an email exchange, when I asked him how the assignment originally came about back in ’87. “And Woolrich had in fact completed it. But the opening was missing, as were perhaps two dozen pages throughout. And there were inconsistencies, including a character who died and then was present again.”

Block was already a well-established, widely published author by the late 1980s. One might wonder why he was willing to leave off from his own original work to complete another writer’s novel then. I asked him what drew him to the project of cleaning up Into the Night.

“I don’t know. Ego and avarice have always been major motivators for me, so they very likely played a role.”

To a reader of the novel, which Hard Case Crime released in a new edition with a revised ending last year, it’s hard to discern where Woolrich left off and Block took over. Credit Block for his ability to seamlessly provide that continuity in the text. When I asked Block how a reader could tell where Woolrich’s writing stops and his starts, he replied, “If I did my job properly, you don’t.”

The story is pure Woolrich, though, in being both moody and filled with disturbing content. It’s an interior tale, and a cerebral one, dominated by the musings of its omniscient, philosophical narrator. The case can be made that more direct action, and dialogue among characters, could have turned it into an even more engaging read. But even with all the lengthy exposition from the narrator, it’s still a gripping yarn peppered with signature noir touches like obsessive desperation in the lead character, a domino effect of one ill-advised decision by a conflicted person leading to several other bad moves by them, a classic complex of a man getting torn between a good girl and a bad girl in his love life, raw violence, etc. And then there are some unsettling plot elements that are more particular to the unbridled creative spirit of the psychologically unbalanced Woolrich. Some of the story’s pieces are far-fetched enough to test a reader’s sustained interest in the tale, but the writing is strong to the point where it keeps you turning the pages, anyway.

I queried Block as to why the decision was made to construct a new ending to the story, and got the answer, “My chief regret over the years was that I had been far too respectful of Woolrich’s draft and had consequently retained a syrupy ending that did not suit the work and was not consistent with the author’s body of work. Charles Ardai agreed, and fashioned a conclusion for the book that is very much what Woolrich would have furnished had he been at the top of his game.”

And when I asked Block what, if anything, he would want to say to Woolrich about Into the Night, if he could:

“Not your best work, Cornell, nor mine either. But neither of us needs to be ashamed of it.”

Brian Greene writes short stories, personal essays and critical pieces on books, music, film and visual art. His features on noir fiction and films have been published online by Criminal Element, Crime Reads, Literary Hub, The Strand, Crime Time, Crimeculture, Mulholland Books, and others, and in print by Stark House Press, PM Press and Paperback Parade. He lives in Durham, North Carolina. briangreenewriter.blogspot.com/Twitter: greenes_circles