Hollywood embodies the title of one of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s worst novels: it’s beautiful and it’s damned.

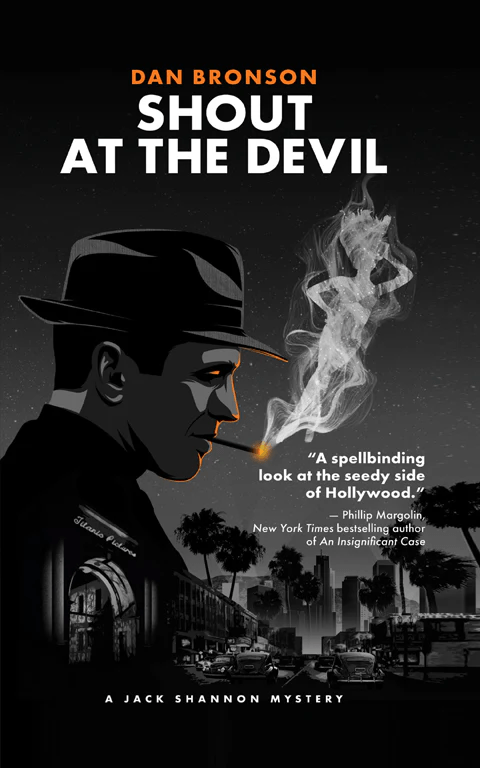

Dan Bronson has led many lives: Associate Professor of English at DePauw University, Senior Story Analyst at Universal, Associate Story Editor at Filmways, Executive Story Editor at Paramount, Writer-Producer of HBO’s acclaimed Ed Harris thriller The Last Innocent Man and ABC’s cult classic Death of a Cheerleader, author of the comic memoir Confessions of Hollywood Nobody and of the hardboiled mysteries Someone To Watch Over Me and Shout at the Devil.

The Last Innocent Man was nominated for Best Writer, Best Director and Best Film in the Cable Ace Awards. Death of a Cheerleader was one of the highest rated Movies of the Week ever made and actually inspired a remake 25 years after its initial airing. Michael Anderson, director of Around the World in Eighty Days, The Quiller Memorandum and Logan’s Run, has said that Dan’s memoir, a fun, funny survivor’s guide to Hollywood, should be required reading in every film school in the country, and New York Times best-selling mystery writer Phil Margolin has compared Dan’s Jack Shannon novels to those of masters like Hammett, Chandler and Macdonald.

I interviewed Dan shortly before the publication of his most recent novel, Shout at the Devil, the second in his series of Jack Shannon mysteries. Like its predecessor, it takes place in Hollywood, this time in 1951, and in it, Jack attempts to help a beautiful star fend off a blackmail attempt only to end up the prime suspect in the blackmailer’s murder.

Why Hollywood?

I was fascinated by it even as a kid. By the movies. By the town itself. Trained there as an actor. I’ve known it intimately most of my life. For me, it embodies the title of one of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s worst novels. It’s beautiful and it’s damned, an embodiment of one of the great literary themes: the chasm between appearance and reality. I used to think Shakespeare said it best—“All that glitters is not gold,” but I’ve come to believe that Hollywood says it better.

Why the noir mystery genre?

It’s the perfect genre for the expression of the appearance versus reality theme. The protagonist in a mystery has to break through the appearance to the reality. It’s also the perfect vehicle for exploring a related theme: the darkness within us all. I used to teach a lit course called “The Beast Within.” The reading list included Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde, Heart of Darkness, “The Secret Sharer.” That sort of thing. Shout at the Devil is a look at the beasts prowling the jungle of corruption that is Hollywood.

In light of that, who are your literary masters?

I grew up reading nothing but science fiction. At age of eleven or twelve, wrote the world’s worst science fiction novel, but by the age of sixteen or so, I discovered Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Steinbeck and Faulkner. After reading A Farewell to Arms, I carried around a book called Hemingway: The Writer as Artist by this guy named Carlos Baker. It was like a bible to me. I did my grad work at Princeton because Fitzgerald went there and because Carlos Baker was on the faculty there. Carlos ended up my thesis advisor on my doctoral dissertation, a study of Fitzgerald’s style and structure. Then, years later, while on summer program in Scotland, a friend there introduced me to Raymond Chandler. A few lines like “A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained glass window” and I was head over heels in love. Read all his novels in sequence. Followed up with other noir masters. Hammett, James M. Cain, Ross Macdonald, Jim Thompson.

Your style is quite distinctive. How did it develop?

From reading hundreds if not thousands of screenplays as story analyst and story editor. When I first came to Hollywood, screenplays were ironically written in big blocks of prose that lay dead on the page. Then I came across a screenplay by this nobody named John McTiernan. OMG! He’d figured it out, writing in short sentences, bombarding the reader with imagery and dialogue, letting the story play out across the page the way a movie plays out against the screen. So I write in short, unadorned sentences and in paragraphs sometimes as brief as a single word. My prose is highly visual in nature and relies heavily on dialogue. The result, I hope, is easy reading—so easy that several members of my informal editorial board of fellow writers read SHOUT in a single sitting. I sent an advanced copy to actor turned writer Jameson Parker. He was in the midst of writing a magazine article and told me it would be a week or two before he could get to it, but the next morning I received an email from him with the heading, “DAMN YOU!” It seems he’d like the title so much that he decided to read just the first page. It turned out he was like Burt Lahr in that old potato chip commercial. He couldn’t eat just one. He was up half the night.

Why the first-person POV?

It’s the classic noir mystery POV, the POV of Chandler, Macdonald, and Cain (at least in Postman and Double Indemnity) and more recently, of Connelly in the Bosch novels and Mosley in the Easy Rawlins book. I love it because it’s so restrictive and so damned hard to do. Your narrator has to be on the scene of or at least have credible knowledge of every important incident. It’s similar to the screenplay, where you have to convey everything in present time through nothing but dialogue, action and imagery. No going inside the minds of the characters. No authorial commentary. No slipping from one POV to another. And you have to make these restrictions work for you rather than against you.

That brings us to the question of the narrator’s voice and of dialogue. How did you find Jack Shannon’s voice and the voices of the individual characters?

This takes us back to those hundreds and hundreds of screenplays that I read. I found that in the best of them, every character had his or her own voice. That the best screenwriters gave their characters voices so distinctive that you didn’t need character labels to know who was speaking. A corollary of this was the fact that every character, even the most minor (like First Cop or Second Reporter) was distinctive. Every character had some trait to distinguish himself or herself from the others. As for Jack, the more I thought about him, about his experiences, about the things that made him who he is, the clearer his voice became. I think you described it best in the blurb you gave me for SHOUT. His voice is “cynical, ironic, self-deprecating, and funny.”

Where did Jack Shannon come from? Where did Someone To Watch Over Me and Shout at the Devil come from? In other words, what inspired these stories. Actual incidents? Real events? Real people?

Jack and the two novels came from my long, often frustrating and demoralizing experience of Hollywood. I often found myself wondering what it would have been like to work under the studio system. Back in the late nineties, I got the idea of doing a series of mysteries set in post-war Hollywood when the studio system had begun to break down. In the years that followed, I decided that my protagonist should be an actor on the verge of stardom, who volunteers when WWII breaks out, and returns physically and emotionally scarred to a town that doesn’t remember him. It only took another ten or fifteen years for me to finally sit down and began to write that character’s story.

I’m curious about your working method. The nature of your research. Do you outline?

My working method? It goes back to my screenwriting days. I used to research the hell out of my subject. Lived in the UCLA library back before the days of the internet and the instant delivery of digitalized books. Then I’d visit the scene of my story and get to know people who lived there. I’d return home and do endless character sketches and outlines. I’d start by figuring out the climax at the end of each act. Then I’d backfill, developing the scenes that would take me from the beginning of each act to its end. Then I’d put all that away, go to the boat my wife and I kept at Channel Islands Harbor, and I’d stay there until I had a first draft. I’d get up early, jog around the harbor hoping to dislodge a few ideas from my still sleepy brain, have a quick breakfast, and walk the beach until the characters in the scene of the day began to speak to me, recording it all into the tiny tape recorder I carried with me. I think it was the sound of the waves turning over, that wonderful white noise that allowed me to slip away to a world elsewhere, the world of my story where my characters began to talk. I’d return to the boat, transcribe everything to yellow legal pads, revising as I wrote, and then after what I call a “creative nap” where I often got some of my best ideas, I’d transcribe the work on the yellow pads to my computer, again revising as I worked.

The process for the novels is similar…to a point. We live in the remote Tehachapi Mountains now. A trail through the woods has taken the place of the beach and the wind in the trees stands in for the sound of the waves. I no longer use the tape recorder or the yellow pads. I type the story directly into my computer. And here’s the biggest change of all. I no longer use a detailed outline. Instead, I work from a broad outline of the plot. And I find that things keep changing as I write. In both novels, I thought I knew who the killer was from the outset, and in both novels, I was wrong. The killer turned out to be someone else altogether. I simply follow the characters where they take me, so I’m often as surprised as the reader by the turn of events that transpire. I think that’s probably why no one on my informal editorial board (or anyone else I know) has guessed the ending of either novel.

One last question. Do you re-read your work.

Never. The same question came up recently for a panel of Mystery Writers of America Grand Masters: Michael Connelly, Walter Mosley and Laurie R. King. Everyone one of them said no. They never re-read their work. I was disappointed when time ran out before I could ask the obvious follow-up question: Why not? Why don’t you re-read your own work. I suspect their answers would have been the same as mine. Because the characters and their stories could never be as vivid, as immediate, as alive as they are in the process of creating them. In the early days of my screenwriting career, I cried as I completed each script. Not because the endings were sad, though some of them were. But because I was aware that I would never again get to know these people again as well as I knew them in the moment of creation.

Stephen Galloway, the former executive editor of The Hollywood Reporter and the current Dean of the Dodge College of Film and Media Arts at Chapman University, is the author of Leading Lady: Sherry Lansing and the Making of a Hollywood Groundbreaker and Truly, Madly: Vivien Leigh, Laurence Olivier and the Romance of the Century.