A small price to pay for a sequence that packed them in at the box-office….

I died three times that day.

The first time I was an Indian attacking a white settlement. The second time I was a member of the posse pursuing me. The third time I was the villain who incited the Indians, shot by the hero and falling from a cliff to my death on the rocks below.

I’m a stunt man. A drugstore cowboy working from Hollywood’s Poverty Row, where the budgets are tight and the schedules tighter. Death is a valuable commodity in my world. In fact, the audience demand for it is what keeps me alive, keeps food on my table and a roof over my head, but the thing is, it’s a presence behind the camera as well as in front of it.

Everyone remembers that rousing climax to The Charge of the Light Brigade, right? It was one thing to hear it from old man Tennyson. “Into the valley of death rode the six hundred.” But it was another, more thrilling thing to see it on the big screen. The gallant Errol Flynn leading a suicidal charge. Cannons to the right of them, cannons to the left, cannons in front of them, they rode and they fell, horses and their riders, shot, crashing end over end, a cascade of tumbling soldiers and their mounts meeting crippling injury and death on a field of slaughter.

Gets the old heart pumping just recalling those images spilling from the screen, doesn’t it?

Words like “electrifying,” “hair-raising,” and “heart-stopping” come to mind.

Well, guess what?

A lot of hearts, most of them equine, stopped during the shooting of that famous sequence. Dozens of horses broke their legs or their backs and had to be destroyed, the victims of a trip wire known as the Running W, which allowed the rider to bring his mount down at designated points in the carnage. Then, of course, there were the riders themselves. A countless number suffered serious injuries. One died, impaled upon his own sword.

A small price to pay for a sequence that packed them in at the box-office!

Now, in fairness, I should tell you that Hollywood has renounced the use of the Running W.

A sign of new-found humanity and compassion?

A come-to-Jesus moment in which the studio heads acknowledged their trespasses and promised to sin no more?

Probably not.

Errol Flynn was so enraged about what happened that he physically attacked the director and lodged a complaint with the American Humane Society, which pressured Congress to intervene. The whole process couldn’t have taken more than four or five years, and now we have it, right there alongside all those other “Thou Shalt Not’s” in the Hays Code: “Thou shalt not mistreat animals in the production of motion pictures.”

Of course, there’s still nothing in the Code about the mistreatment of human beings. An oversight, I’m sure. After all, the studios are meticulous in the way they track and control the high cost of making movies. Their detailed budgets track every expense down to the last penny. It surely won’t be long before they start to calculate the human cost of what they do.

Right.

Anyhow, back to my story, which is, in a way, a record of that human cost.

It was Sunday, the last day of the shoot for this seven-day wonder of ours. (The majors get six weeks or more. We get one.)

I won’t bother you with the plot, other than to say it was something you might possibly have seen before. You know, the sort of thing you get when you blend a White Hat, a Black Hat, a Beautiful Maiden and a handful of Indians. Stir well, bake at 110 degrees in a convenient desert location, and voila…

A cliché western to be served up as the second course of a double bill at your neighborhood theatre!

We were on location in the Alabama Hills outside Lone Pine, California—a sprawling fantasy of rock rounded and sculpted by time into boulders, fins, arches and monoliths. Some of them were horizontal, spilled across the sand; others rose vertically in grotesque walls.

I was on top of one of those walls, costumed as the villain of our sagebrush epic, about to meet my death on the rocks forty feet below, rocks that concealed a bunch of cardboard boxes stacked eight feet high and covered with mattresses.

A shrill whistle ripped through the air, signaling the director’s call for action. I took the hero’s imaginary shot, spun around, and plunged backward to what I hoped would be my imaginary death.

My hopes were realized.

I hit the center of the landing pad, and as I lay there, staring up at that smog-free desert sky, I heard a distant buzz. The buzz became a roar, and a silver streak flashed by not a hundred feet over my head.

I crawled off the pad and onto the rock, tracking the open-cockpit monoplane as it grew smaller, dropped its left wing in a tight turn, and came screaming back my way, a rocket with wings and wheels—more 2051 than 1951.

Straight overhead, it tipped its wings in a kind of aeronautic howdy, and I caught a glimpse of the pilot in the rear cockpit, his face covered in goggles and leather headgear.

Then almost straight up…

…into a loop…

…a barrel roll…

…and a swoop down to flare and land on an abandoned rancher’s airstrip on the plain separating the Hills from the dizzying peaks of the Sierras.

As I made my way down the rocks to the crew on the sandy floor below, the gleaming silver aircraft taxied to the edge of the plain and swung around in a tight turn, positioning itself for take-off. The engine coughed and died, and as the prop jerked around in a few final slow turns, the pilot, in a dark blue flight suit, pushed himself up out of the tight cockpit, stepped down onto the wing and then the ground, and as he moved forward to meet the crew rushing his way, he pulled off the goggles and the leather headgear, exposing long blond hair pulled back in a matted, tangled ponytail, revealing that he was a she.

Karen Scott, of course.

A star who knew how to make an entrance.

CHAPTER 2

Karen Scott.

Sultry. Sensuous. Sassy.

A cascade of blonde hair covering one of her blue, blue eyes in a peek-a-boo, come-hither look that drives men to madness and women to envy.

At the same time, her own woman.

Strong-minded, feisty, she takes nothing from anyone, and if you cross her, especially if you’re a man, watch out!

That’s the Karen Scott of the screen, the Karen Scott you know from Midnight Madness and a dozen other hits. The shocker, at least for those of us who work behind that screen, is that the real Karen Scott is the identical twin of the movie star, only five foot one but as big in life as she is in moving pictures.

Now, Karen and I had a history.

What, you ask, would a sensational woman like her have to do with a mug like me?

A muscle-bound Poverty Row stuntman and extra with a bayonet scar across the side of his face. A truant self-educated in the school library while serving time for misbehavior in class. A bindlestiff who served another kind of time on a chain gang in a part of the South where poverty was a crime. A rough and tumble cowpoke who worked his way west riding the rails and the range.

What would a classy guy like me be doing with a woman like her?

The answer?

Acting.

In a picture called Bridger’s Gap.

I’d arrived in Hollywood, registered with Central Casting, and started hanging out at the Columbia Drugstore along with dozens of others, some of them refugees from the ranches closing all over the west, others who’d have been hard-pressed if quizzed to tell one end of a horse from the other, and a few who could have played its hindquarters.

The owner of the store generously let us use the payphone inside to check in with Central Casting every afternoon to see if any extra work had come our way and, of course, to spend any spare change we might happen to have had on the snack food he just happened to sell.

Most of our work, however, came not from Central Casting and the majors, but from the super low-budget producers who worked right across the street on what was known as “Gower Gulch” or “Poverty Row.” They’d show up at the Columbia, wander through the crowd of cowboys gathered there (pre-costumed or, rather, free-costumed in their Stetsons, jeans and boots), and dub the lucky few among us employed. Then, off we’d go to a rented studio or a free location to stand around and serve as “background.”

And there you have it, folks…the story behind the story of the drugstore cowboy.

One morning, I got lucky.

Now, remember, this was in my pre-scar days when, I’m told, I wasn’t too bad looking. I checked in with one of the operators at Central and learned that Titanic Pictures wanted me for a small speaking role in the western currently shooting there. You see, when you registered with Central, you listed your various skills. I must have put down something like “Capable of speech” or “Talks without stuttering.” That, I’m sure, would have gotten a derisive laugh out of some of my friends, but the thing is, most of us lied shamelessly about our talents. Anything to get the job.

I got the job, and then I got lucky again. It was the first day of the shoot, and the lead actor showed up hopelessly drunk for a big scene opposite Karen, who was doing her first major role. While the director and the producer conferred on how to deal with the crisis, they had me running lines with Karen. At some point, they started to listen to the two of us…and they solved their problem by casting me in the drunken actor’s role. It was clearly an act of desperation, the sort of thing every aspiring actor dreams of, the sort of thing that never happens, but it was a low-budget programmer, the stakes were anything but high, and it paid off.

Bridger’s Gap became a hit. Karen was off to a career of super stardom…and me, I was off to war.

A lot of water—in my case, much of it turbulent and dirty—had passed under the proverbial bridge since then, but through it all, Karen had remained my friend, and now, here she was again…recognized by no one but me.

When I said that she was the same person off the screen as on, I was talking about her character—her toughness, her feistiness, not her appearance. The fact of the matter is that she could walk down a crowded street, and even though she was one of the best-known faces (and figures) in America, no one recognized her. With her signature hair pulled back in a ponytail and her fabulous figure lost in a loose dress (or in this case, a flight suit), she was just another attractive woman.

It was a great blessing.

Unlike most stars, she did not have to contend with the downside of fame, with instant recognition by total strangers convinced that they know you intimately from the roles they’ve seen you play, who want, more than anything else, to be your friend.

Karen laughed about it. Said it kept her humble (though I myself have some doubts about that.) In any case, our skeletal cast and crew rushed out to her not because they knew she was a star. They didn’t. What they were sure of was that she was one hell of a pilot, and they peppered her with questions about her plane, which, it turns out, was a Ryan STA, designed and built by the guy who gave us “The Spirit of St. Louis.”

Made sense.

If there was one thing Karen had plenty of, it was spirit.

Our director, hot in silent film until he had an ill-advised affair with the wife of the man heading the studio he was working for, was in the habit of blocking and rehearsing a shot and then dozing off between set-ups, sometimes sleeping through the shot itself. This afternoon was no exception. He had slept through the shot, the fly-over and the landing and was, in fact, still sawing logs in his canvas chair underneath the umbrella shielding him from the sun.

However, Bob Burr, our fearless Assistant Director and Stunt Coordinator, who may not have been rabid but who foamed at the mouth on a regular basis, stood in for him as usual and raised hell with Karen.

“What the fuck did you think you were doing? Your damned antics could have ruined the shot!”

Karen stood her ground.

“I was putting on a show. You know. Like Mickey and Judy.”

Bob’s hands balled at his sides; his face split with rage.

“Jesus Christ!”

Then Yours Truly—he of the uncontrollable mouth—joined the conversation.

“Watch your language, Bob. That’s a lady you’re talking to. You got your shot. I finished the fall before she showed up. No harm. No foul.”

He turned to me, his face almost purple now.

“I want any shit out of you, I’ll let you know. In the meantime, you’re fired!”

For the fourth or fifth time on this shoot.

I took my dismissal with the seriousness it deserved.

“Check the schedule, Bob. It’s the last shot of the last day of the shoot. As A.D., you should know that.”

He took a step toward me, hesitated…and then made what was probably a wise decision, turning to the cast and crew and announcing it was time to pack up and go home.

As they went to work, Karen grinned.

“You seem to be really good at losing jobs.”

“Yeah. Well, in this case, I had some help, didn’t I?”

She shrugged modestly and pulled her flight suit zipper down far enough to get some relief from the desert heat (and, of course, to make it clear that she was wearing no bra).

“Whew! Hot down here.”

Whew indeed! And yes, I had to agree. It was hot. Very hot.

We continued our conversation as the crew broke down the camera and its lenses, gathered up cables and tripods, apple boxes and shades, chairs and umbrellas, carrying them past us to the equipment trucks waiting not far from the plane.

“So, you’re a stunt pilot now?”

“I’m an actress. In my case, that’s a stunt. A big one.”

“Well, you always did fly by the seat of your pants.”

“And yours, on several occasions.”

I laughed.

She winced as a crewmember carrying a big silver reflector passed by, inadvertently dragging the focused rays of the sun over her eyes, and her playfulness turned suddenly serious.

“We need to talk.”

“Sure.”

I could have led her to Gene Autry Rock, where I always expected to see that stalwart of the Old West, riding along, crooning to the accompaniment of an unseen orchestra.

Hollywood realism at its best!

Or we could have visited the site of the suspension bridge that Cary Grant and Sam Jaffe took over that bottomless canyon in Gunga Din. Unfortunately, the bridge is gone, and so is the canyon. As a matter of fact, the canyon was never there to begin with. Just the two rock formations connected by a rope and plank bridge that was only about six feet off the soft, sandy ground.

Unsurpassed Tinseltown magic!

The possibilities were endless, but it was clear to me that Karen, in spite of her stunts and her jokes, was in no mood for a tour. We ended up on the back side of the monolith from which I’d just fallen to my death and sat down on a couple of convenient bench-like boulders.

She stared down at the sandy soil.

Then lifted her eyes to mine.

“I’m being blackmailed.”

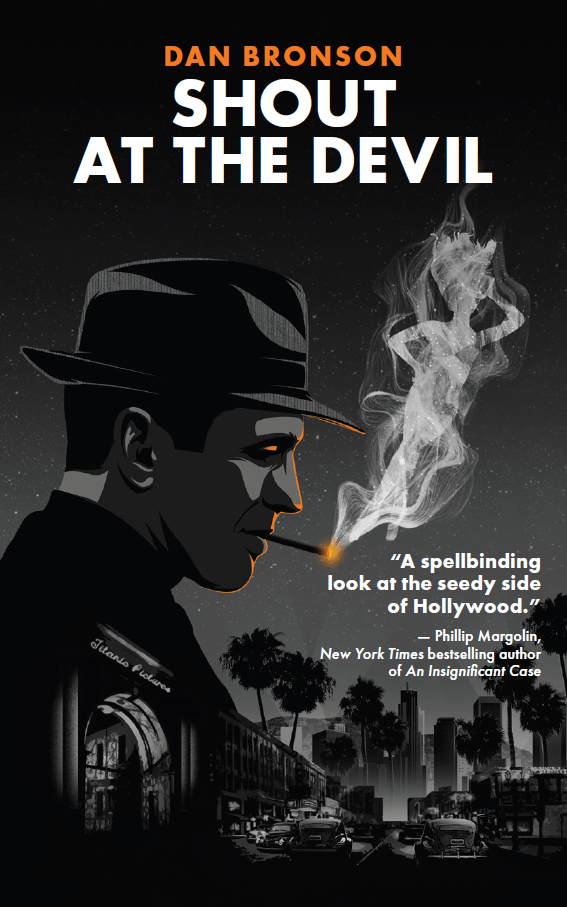

The above is excerpted from Chapters One and Two of Shout at the Devil by Dan Bronson (BearManor Media, 2024).

Dan Bronson has had many careers: college professor, story editor, screenwriter/producer, memoirist, and now, novelist. Dan-Bronson.com