Bill does have that quirky loser quality, but with a bit of honor and dignity beneath his gruff exteriors. This is similar to characters in Goodis, who was thought of as “poet of the losers.”

Scott Phillips’s novels The Ice Harvest (2000), Cottonwood (2004), and The Left Turn at Albuquerque (2020) are considered modern masterworks of western neo-noir. Phillips draws on the vast traditions of both to create works of startling violence and unexpected hilarity. Always unpredictable, and wildly fascinating, Phillips’ work is consistently refreshing amongst the other rehashed noir efforts out there.

Throughout a recent interview via Zoom, we talked about contemporary and classic noir authors such as Donald Ray Pollack, Jim Thompson, and Charles Willeford, the relevance or irrelevance of noir, and various changes in the capture of images from early photographs to the dawning of cinema. Phillips had a wealth of stories and anecdotes about his experiences in the publishing and film industries.

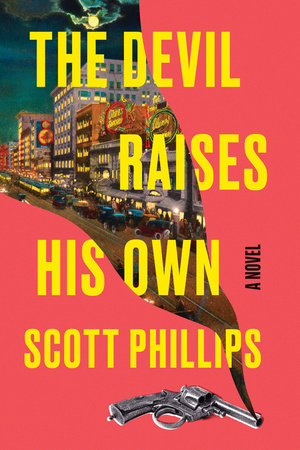

Phillips newest novel, The Devil Raises His Own (Soho Crime), is a raucous foray into the seedy underworld of early Hollywood and immerses us into the grimy porn “blue movies” industry of that era. His main protagonist, who has appeared in a number of Phillips’ novels, is Bill Ogden, a successful photographer who stumbles upon disturbing events, including brutal murders. By his side is his granddaughter, Flavia, who is emotionally recovering from having recently bludgeoned her abusive husband to death.

Phillips’ work maintains a dark, wry sense of humor and his prose crackles in a manner akin to reading an early tabloid with a literary bent. Phillips draws upon a diverse and often grotesque group of characters and brings them together into what essentially can be likened to the wild-west as in the early days of Hollywood.

What is it about “blue movies”, porn and technology that is significant at the turn of century Los Angeles that acts as the centerpiece of this novel? What does the technology have to do with their production?

I’ve always been interested in film history, and parts of my family have always lived in Southern California. Every new form of media immediately attracts pornographers. In the first book in which he appears, Cottonwood, Bill Ogden makes pornographic stereo views in the 1870s, mostly for his own consumption. People started making dirty movies at the dawn of cinema. In those days, they were circulated clandestinely to lodges and such in great secrecy, since making, distributing, possessing or exhibiting them would have been criminal, not to mention the social disgrace involved in getting exposed.

Are these movies still in circulation?

They were classic ephemera, not really meant to be seen more than a few times, certainly not meant to be archived or studied. Nonetheless a good many still exist, and they’re as explicit as anything on the internet today.

How is this novel different from your other work?

When I wrote Cottonwood twenty years ago, I knew I wanted the protagonist to be a frontier photographer. Yet It’s different from the other two books with Bill Ogden in that it isn’t in the first person and it’s told from multiple points of view.

You mentioned that you loved Charles Willeford and were reading his “lost” novel? Hoke Mosley is an interesting character? Why does he appeal to you? What do you like about Willeford? Also, Jim Thompson?

It’s been years since I read it, actually. It’s called Grimhaven, and the title is appropriate. Hoke is appealing in the same way all Willeford’s protagonists are. He verges on the psychopathic, but you’re with him all the way. Someone called CW “the master of the asshole protagonist.” Thompson is similar in that he’s just a few drops of humanity away from being a complete nihilist. Also they’re both funny as hell; the only noir novel I find as funny as CW’s The Woman Chaser is Thompson’s Pop. 1280.

Your chapters are short and punchy. There is a lot going on and many different stories converging. How did you plan out all the subplots? How do you keep track of them? Why did you structure the novel this way? Were there other writers and filmmakers who influenced you in this way?

Originally the book was going to be first person, from Bill’s POV, but the other characters were jostling for elbow room. The two books I was really trying to emulate were The Heavenly Table by Donald Ray Pollock and The Given Day by Dennis Lehane, big sweeping historical novels with lots of characters and no romanticizing the past.

I write for an imaginary reader who is exactly like me in taste and temperament. When I started doing that instead of writing for an imaginary marketplace, that’s when I started getting a little success.

You mentioned Donald Ray Pollock’s The Heavenly Table as an influence? Why this novel over the others?

That book and also Dennis Lehane’s The Given Day both presented big tableaux of American life early in the twentieth century, with big casts of characters and sprawling plots, and I wanted to do something like that. Another book that influenced me, though I wasn’t thinking about it at the time, was Day of the Locust by Nathaniel West, probably the best book anyone will ever write about Hollywood, as bleak and true today as it was in the 1930s.

Bill is a great protagonist. How do you see him in place in line other noir characters?

He does have that quirky loser quality, but a with a bit of honor and dignity beneath his gruff exteriors. This is similar to characters in Goodis, who was thought of as “poet of the losers.”

What inspired you to create a protagonist that is a photographer?

I’ve been a photographer since my teens, and I was a pro for a few years, and the history of the medium interests me. And I wouldn’t say Bill is a loser; he gets into a lot of trouble, but he’s made a success of himself and he’s a proud professional. He doesn’t avoid the company of losers, on the other hand.

What did you think of the cinematic adaptation of the Ice Harvest?

I loved it, it was a great experience. Everybody treated me really well and I’ve still got friends I met through the making of it.

Didn’t a certain Boston journalist call your work on the The Ice Harvest “another attack in the war on Christmas? What do you think of that review?

That was their book critic. She was horrified that a novel set at Christmastime would have sex or violence in it. That one made me laugh. I didn’t mind, there’s a certain kind of negative review that will make me seek a book or movie out.

What was it like to work with Billy Bob Thorton, Harold Ramis, and John Cusack on the Ice Harvest? Any interesting stories?

It was a great experience. I only met Billy Bob once, on set. I’ve met Cusack a few times, and he’s a nice guy and obviously a huge talent, but I can’t really say I got to know him. Harold Ramis and I got to spend a lot of time together after the film was made and got to be pretty good friends. We went to the Deauville Film Festival in France with Connie Nielsen, who played Renata, the femme fatale, and I got to be good pals with her as well. On the press junket she sensed that all the journalists wanted to talk to her and Harold and not me––which I completely understood––and she thought my feelings might be hurt, so she told the French publicist “I want Scott to be there for all my interviews to help explain my character,” and the publicist (a dour fellow who had taken a dislike to me after I inadvertently insulted his friend Roman Polansksi during dinner) said absolutely not. She stuck to her guns and I did all her interviews with her. The journalists were politely uninterested in talking to me, but I was really moved by her gesture. Really a nice person.

Who is your audience? Do write for yourself? Why?

I write for an imaginary reader who is exactly like me in taste and temperament. When I started doing that instead of writing for an imaginary marketplace, that’s when I started getting a little success.

What do you think of literary critics? Are you afraid of bad reviews?

I actually have a lot of friends who are critics. I’ve been very lucky in terms of reviews over the years. A critical review doesn’t bother me unless it’s malicious, or just incorrect, like the woman on Amazon who hated the Ice Harvest because, in her words, it was about a drug pusher. Which it fucking wasn’t. And when I get a review that criticizes a book for being smutty I have a good laugh.

Have most of your reviews been positive? You were said to be a “master of Western noir”.

A publicist called me that. I’m not sure what it means, but I’ll take it.

William Blick is a film and literary/crime fiction critic; a librarian; and an academic scholar. His work has been featured in Film International, Senses of Cinema, Film Threat, Cineaction, and CinemaRetro, and he is a frequent contributor to Retreats from Oblivion: The Journal of Noircon. His crime fiction has been featured in Close to the Bone, Pulp Metal Magazine, Out of the Gutter, and others. He is an Assistant Professor/Librarian for the City University of New York.